Photography credit: Eugene Langan

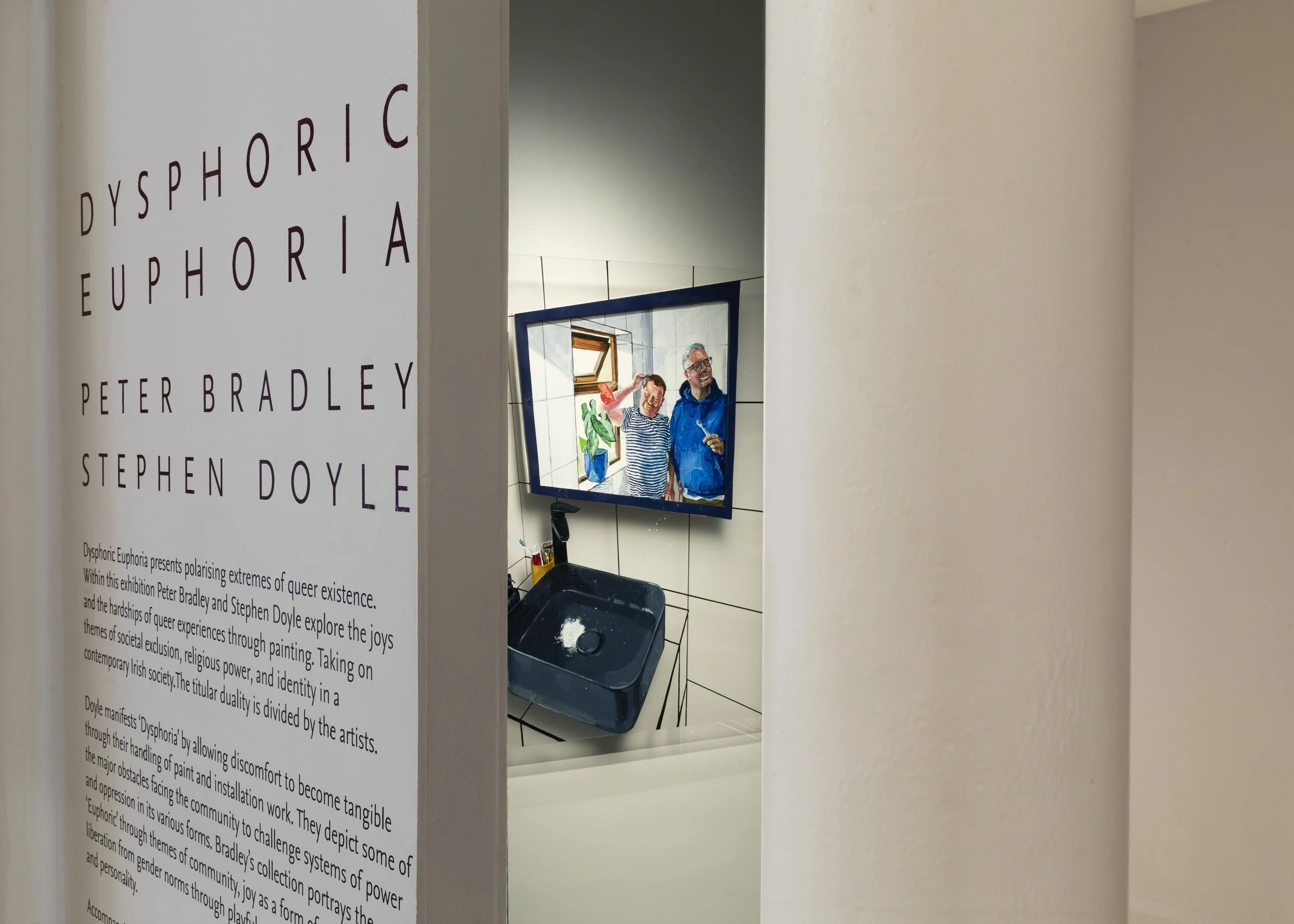

Dysphoric Euphoria

28th June to 10th August 2025,Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda

On Living in the Swerve

Dr El Reid-Buckley on Peter Bradley and Stephen Doyle’s Dysphoric Euphoria at Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda, June 2025.

Throughout his writings, Leo Bersani mediated on ‘the swerve’: the ways in which desire, subjectivity and identity are disrupted, dismantled and, in some cases, radically disintegrated within a queer body. Yet despite his negative lean, he finds potential in the immediate, whereby we can redefine our relations to ourselves and one another; a kind of future against an idea of ‘pure’ progress. There is an inherent rupture in Bersani’s theoretical writing that demands a break in the binaried options of queer pessimism or utopian futurity. In a similar vein, Peter Bradley and Stephen Doyle’s Dysphoric Euphoria leans into the swerve; through figurative and still life painting that trace queer time against the normative modes of being.

Bradley and Doyle’s show mediates on contemporary queerness in Ireland, yet the artists take two different perspectives. On the one hand, Bradley’s work is playful and often camp, highlighting experiences of queer joy and learning to become oneself, or perhaps rather, learning that one can be many selves. On the other hand, Doyle’s paintings are darker, exemplifying the constant, rising threats that queer and trans people are faced with daily, that seem to bubble through all realities and realms. While initially, there seems to be clean and clearly defined differences between the two artists’ bodies of works in this show, upon closer inspection we can encounter the one million invisible ghosts that join the works together. Instead, the artists collaboratively shift between pain and beauty, but never settle on either. To separate those feelings that Bradley and Doyle visualise–euphoria and dysphoria, respectively–and make them into binary opposites is in of itself impossible in a queer logic that always defies dimorphism. Rather, both artists wrangle with the in-betweenness of it all, how queerness can transform and remold itself quicker than it is made.

Bradley’s works push against the ‘straightening’ powers of heteronormativity that attempt to make queer bodies and lives fit into the narrow constraints of what it means to be ‘normal’. Instead, these paintings lean heavily into the euphoric capacities of queerness, where memory, time and bodies move in fluid motions. In the “Pink Triangle” triptych, there is a vivid ecstasy that uniquely captures queer joy on the site of the dancefloor, where many of us, for the first time, became ourselves. It is in these often-furtive club spaces where queer and trans folks find catharsis, no longer limited in their self-expression or expected social performances. While Bradley captures the beauty of newfound embodied individual agency, the figures in these works also seem to blur together, collapsing the fixed borders that separate the self from the other. In essence, the triptych focuses on the generative sustenance afforded through queer social reproduction in spaces and bodies that often repulse a notion of social reproduction at all. Rather, “Pink Triangle” offers audiences a snapshot into how we make and remake ourselves through one another; through the sway and the swerve, in moments of scintillation.

Similarly, Bradley’s “Lavender Boy” visualises the different aspects of social, historical and cultural influence on developing his understanding of his own queerness through still life. While there are more obvious signifiers of this through books and badges, there are also subtle signs through his mother’s cardigan and a curtain tie in a pseudo-croisé devant pose, which gesture towards the fluidity of gendered performance of queer bodies. This is further explored in his mixed-media collage series, “Fruit Machine”. In scavenging found fashion images, and through playfully layering colours and textures, Bradley alchemizes these bodies in dream-like and more-than-human ways; all iridescent skins and shapeshifting faces. Through these works, Bradley demonstrates the possibility of a queer body that can shift, change and represent desires beyond what exists in the past or what could be in the future. Instead, there is a warmth through the neon-drenched potentiality of what can happen in the here and now.

These euphoric resonances that move throughout the show culminate in “Boy with Horses on the Seashore”, a reimagining of a childhood photo where Bradley places his boy-self on a giant My Little Pony figurine: her butter-golden head reared proudly towards the sky, while her plastic pink mane and tail twist and turn, just like the “Lavender Boy” curtain tie. What is profound about this piece is that it is just as familiar as it is unfamiliar, where the ‘gap’ of the real horse is replaced by a queerer (desired) memory. In all its magic and mysticism, it compliments the works presented by Doyle through its uncanniness, whereby the presence of the figurine represents the subversive qualities of queerness, while simultaneously acknowledging its deviance in relation to cis-heterodominant cultures.

Stephen Doyle’s presentation of works wrangles with the many-headed hydra of rage: from fury at the rise of fascism, to an outcry of anger at the ever-shrinking existence of queer spaces. Doyle’s collection, though critical, harnesses such rage as political force and uses it as a palette for their paintings. In “Anathema”, a disembodied Christ surveys the world, headless. Behind the hanging head of Christ, a mirror is cast unto all of us in the buildings below, where thousands more (headless) silent Sons of God still stand, and stare motionless in all our everyday spaces. Doyle’s positioning of Christ’s head away from the mirror suggests a refusal of the Church to face up to its sins, hiding from its own hypocrisy while continuing to exert enormous power socially, institutionally, spatially; unafraid to take up room.

Doyle’s collaborative painting with FELISPEAKS, “Bent Bastards”, emphasises the weaponisation of language against marginalised and minoritised people, whereby we no longer get to decide who we are, but rather it is the others–ironically, the outsiders of our lives–who instead forcibly name us. Draped in derogatory banners, Doyle looks on, and FELISPEAKS looks out at the audience who watches them. While the slurs fall around the figures, there is a quiet strength in the painting that is not just built from reverse discourse, where Doyle and FELISPEAKS might reclaim their ‘bentness’. Rather, the queer bodies–queer in all of its expanded meanings to signal outside normalcy–look outward, onward and inward extending their gaze far beyond the boundaries of the painting, penetrating the powers that define identities into narrow categories. In doing so, it doubly challenges conceptions of our allegedly progressive ‘New Ireland’ that celebrates equality, diversity and inclusion. This is a theme which is also illuminated in the ember light of “A Relentlessness”, where the central figure is subsumed by far-right social media content, and cannot look away from its horrors. In a sense, it offers the inverse of “Anathema”, as those with less power within society have no choice in overlooking oppression, but instead must bear the brunt of it.

Despite the negative affect which seems to dominate these works, there is an overt comfort and safety in “Our Nest”, where the figures of Doyle and their partner, reclined and splayed in ways that push against the normative standards of sitting. Here, Doyle shifts the colours to more gentle pastel pinks and purples. The audience’s view of how these queer bodies fold into one another lovingly, however, is also obscured by a thin, white transparent curtain. Much of recent positive developments in LGBTQIA+ liveability in Ireland has required the sacrifice of a total divulgence of personal and intimate matters, but here, this access is on the couple’s own terms. In a sense, it mimics the nature of Bradley’s triptych, but with inverted intentions unsettling notions of where we can be ourselves, and where we can make home in these fleeting, fluctuating spaces that are consistently subject to scrutiny.

In all its fullness, Dysphoric Euphoria is a testament to what it means to live in the swerve, particularly in these uncertain and ruinous times that attempt to straighten all in its path. It shows a diversity of queerness, in the thick of where we are, despite everything, making and remaking ourselves. The combined works of the artists show that the pleasure of being many selves is not always a privilege, and it does not always feel good. But the deep emotional dimensions of Bradley and Doyle’s paintings let us lean into all feelings. For feeling–good, bad or in-between–is what reminds us that we are human in a world that routinely tells us that we are not, or has refuted that we have ever existed. Instead, the question Dysphoric Euphoria asks all of us–not just queer people–is: I exist and you exist, so how might we exist together? Because while the times we live in are unsettling and uncertain, there too must be bounty and beauty; nothing settles in the swerve.

Photo credit: Emilijia Jefremova

Photo Credit: Marc Jennings

Photo Credit: Marc Jennings

Photo Credit: Marc Jennings

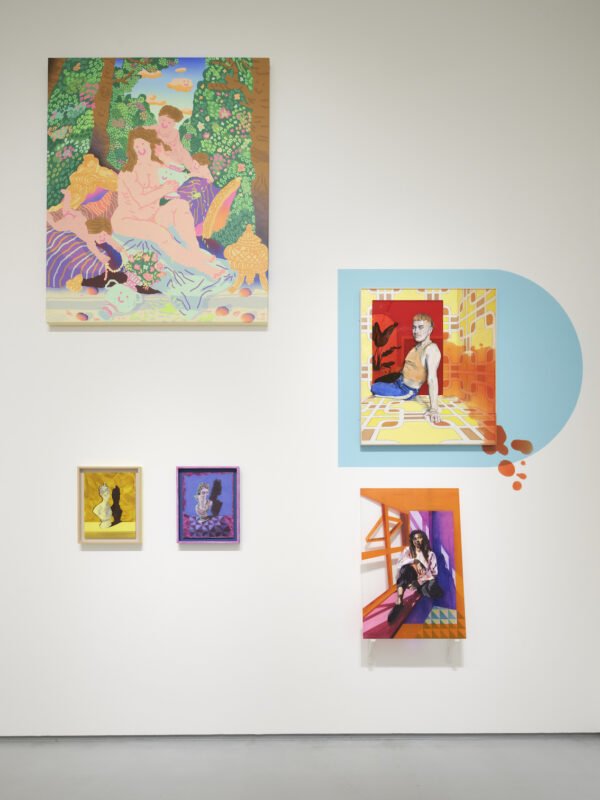

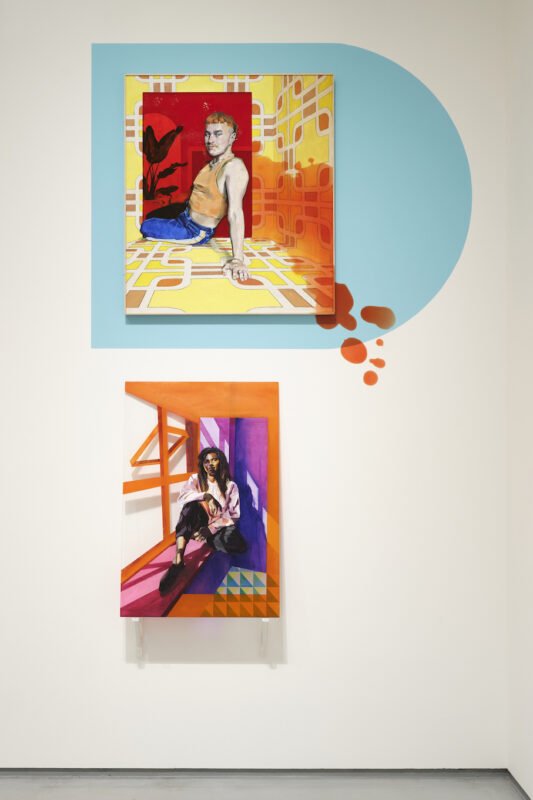

Kaleidoscope

July/August 2024, Galway International Arts Festival, Outset Gallery

Inspired by the diversity of creative identity in his hometown of Galway, Bradley has combined traditional methods of painting, photography, collage and flat sculpture with a modern formalist construction to harness light and shadow. Bradley was shortlisted for the Hennessy Portrait Prize in 2016 and Zurich Portrait Prize in 2018.

Curated by Tom McLean @tommclean_art, Co-Director, Outset Gallery @outset_gallery

Exhibition text by Meadhbh Meadhbh McNutt (@meadhbhmcnutt).

Experimentation is not too different from a workout, in that you have to warm up with small gestures before the body feels safe enough to explore uncharted territory. “Honestly, I didn’t start taking collage seriously until two years ago,” Peter tells me. The sun is pouring through his studio window, sending refracted light across glossy paint, resin and the snouts of two curious, handsome dogs that have wandered in unexpectedly. When I moved to Galway in 2019, one of the first things I did was visit Plane / Potty, an exhibition at the 126 Gallery by Peter Bradley and Laura Angell, curated by the late, beloved Stephan Roche. In this exhibition, the figures in Peter’s paintings had begun to spill out into 3D space, and a small set of collages on acetate sat understated in the corner. The works that I see today attest to the power of these small experiments. “I started working with collage for the first time during Plane / Potty and they always felt like throw-away, preparatory works. I’m coming around to the idea of collage as a finished piece now.”

As Peter began to scale up on acetate, he couldn’t help but be a “bit precious” with the work. So began the experiments with paint on primed paper. “I had a show in the Linenhall Arts Centre in Mayo in 2022; I had a tight timeline and I knew I wanted to incorporate paint on resin. I would have needed months if I were to construct the board, fill the resin, prime and paint. I cut that time in half by constructing the board and resin, and painting on paper at the same time. I could then chop and layer the painting on resin. It was one of those lightbulb moments.”

“I had to pare things back, and collage became the creative mechanism that allowed me to get lost and surprise myself.”

Making the move to become a full-time artist in 2022, Peter finally had some time to think about his practice again and to start a course at the RHA (Royal Hibernian Academy of Arts). ”After four months of thinking, I was back in the studio and it was time to start working. I had to pare things back, and collage became the creative mechanism that allowed me to get lost and surprise myself.” Sometimes, our more silly, throwaway ideas can tap into something unexpected and powerful. This is an essential component of the concept of ‘camp’ that works its way into comedy, performance and design. In her 1964 essay, Susan Sontag said of camp,

“You’re expressing what’s basically serious to you in terms of fun and artifice and elegance.” (1)

I ask if there is an influence of fashion, camp or performance in Peter’s work, gesturing to a red monochromatic painting of a woman speckled in diamanté gems – a look that serves both Dune empress and Doja Cat at Schiaparelli. “I’m really inspired by fashion photography but art college beat that out of me,” he responds. “If you want a career in fine art, you can’t be inspired by fashion – apparently. Funnily enough, in that course I did in the RHA, one of the tutors said, ‘You’ve got a real eye for fashion and composition.’ So, that is something I’m going to start incorporating more.”

“I love that mishmash of everyone’s creativity.”

This influence also stems from those pictured in the paintings: among them, playwright, musician and actor Ikenna Anyabuike; drag performer, artist and musician Leigh Greally; and designer and creative Virtue Shine. “In past shows, I always had one painting of each person. This time, I chose a smaller number of people that I’m really interested in and created multiples.”

Creatives in Galway depend on each other for support, and a snapshot of this community is set in stone in Kaleidoscope. “Virtue is a fashion designer based in Galway, originally from Ghana,” Peter says. “Motifs based on the traditional Ghanaian patterns that Virtue uses in her designs are a focus in her portraits. The idea for Ikenna’s pieces is very much related to words, so I knew he would be a good collaborator. When I met with Leigh, it was also so easy. They’re a performer, so they knew what they were doing. I love that mishmash of everyone’s creativity. That’s why I tend to work with creatives,” he adds. “They know the craic,” we say, concurrently.

“I was thinking about how identity has nothing to do with your body – it’s a matter of how you present yourself. But after a while, I thought, maybe that’s not entirely true.”

Though conceptually rooted in identity, Peter’s work doesn’t cling too tightly to an overarching concept. Identity reads here as something fluid and relational, but with integrity. Compositions and gestures are informed by conversations shared between artist and subject. “In my earlier pieces, I was thinking about how identity has nothing to do with your body – it’s a matter of how you present yourself. But after a while, I thought, maybe that’s not entirely true,” Peter says.

“Maybe your physical self does play a part. So, that conversation is happening here. In some of the works, the figure is removed, and in others, the clothes are pared back. Both can be true at the same time.” The expression of identity, gender and sexuality on a spectrum shines through in the work. Peter hopes that the work will start conversations, rather than shutting them down. “In the 80s and 90s, everybody was focused on the gay thing, and now it’s the trans community,” he adds. “I’m like, ‘Wait until you’re exposed to the idea that sex also exists on a spectrum…’” Quietly political, the work is a refreshing break from the divisive binary of ‘biological determinism’ versus ‘identity politics’ that is too often carted out in politics and media platforms.

If traditional portraiture is solid and conclusive, this kind of relational painting presents a more 360 view – however fragmented. For Peter, the idea that collage could mirror identity – a living, refracted thing – was a happy realisation. “The separating of a person into layers; each layer has an effect on the other. Light plays a big part too. The work changes with every momentary shift of light and reflection in the room. This painting will never be perceived in one, singular way

– and I love that.”

(1) Sontag, Susan (2018). Notes on Camp. Penguin Classics.

Photo credit: Ros Kavanagh

Photo credit: Ros Kavanagh

Photo credit: Ros Kavanagh

Photo credit: Ros Kavanagh

Photo credit: Ros Kavanagh

Photo credit: Ros Kavanagh

Generation 2022

New Irish Painting, a celebration of painting and of painters at work in Ireland today.

April - July 2022

With established or burgeoning careers, the works by the artists on view reflected a diversity of approach to painting, from abstraction to figuration, to representational work embracing landscape and portraiture. Some paintings were incorporated into installations on the wall, but mostly the works were two-dimensional explorations of the variety of the passions, issues and concerns of the individual artists. In my research for this exhibition, I visited studios in many parts of the country—from Belfast to Ballydehob—and encountered vastly different working situations. From the light-filled spaces of Queens Street Studios, I went on to view works on kitchen tables, walls of apartments, in spare bedrooms and attic spaces to a windswept chalet in West Cork. No matter where I travelled I encountered artists at work doing what they love to do. Post pandemic we were equally thrilled to be looking at and talking about art which made these visits a rich and rewarding experience. My intention when curating this exhibition was not to mount a survey of painting but to reflect a personal observation of the quality of painting I saw happening around the country. The works are hung salon-style, embracing the height of our Main Gallery while providing space to view the work of the twenty-six artists on show.

This group of exceptional painters are undeniably leaving their mark and making an impact on the contemporary art world in Ireland today. If this exhibition does nothing else I do hope it leaves you with a desire to seek out more of the individual work of these artists through their websites and galleries and to view more of their work in person—the rewards will be immense.

Anna O’Sullivan

Director/Chief Curator

Sonder

January/February 2022, Linenhall Arts Centre, Castlebar

For this collection Bradley has used a range of materials to create an interactive and engaging experience. Using transparency, light, and reflectivity in his work has allowed him to analyze the reciprocal relationship between the viewer, the work, and the environment. If the movement of the viewer has an effect on their perception of the piece then they become part of the work, unique in that exchange. The perceived effect of their actions on the work is designed to make them think about how our actions affect those around us.

NO RULES

October 2021, 126 Gallery, Galway

Sometimes things may not make sense. You need to navigate a space to gain a different perspective. Sometimes things won't ever fully make sense. Maybe you don't need to understand it to appreciate it.

There are infinite layers and elements to an individual's identity.

There are No Rules.

Plane/Potty

Two Person Exhibition with Laura Angell at 126 Gallery, Galway, 2018

Our identities are composed of a number of elements; how we feel, how we look, who we love, and how we choose to present ourselves to the world.

A painted portrait is similarly constructed through a selection of fundamental elements; the figure, the environment, the surface, the frame, all relating to each other in a particular way to form a representation of the subject's identity.

We understand portraiture by relating it to ourselves, much like we relate to everything else around us. When the expected formula of elements in a portrait has been interrupted or distorted, we are forced to shift our perception of what we are seeing in order to make sense of it. We are compelled to think differently about the subject and our connection with them, but is it possible to understand the lived experience of someone who identifies as a different gender, sexuality, or race to you? Or is that akin to attempting to understand alternate planes of reality?

This body of work is a commentary on the perception of portraits and their subjects, and an investigation into acceptance of and respect for what we may not understand.

Praxis

Degree Show Collection, Limerick School of Art & Design, 2014

This body of work examines the diversity of gender as a practiced and performed social construct while also confronting our habitual conflation of sex, gender, and sexuality. Having engaged extensively with a number of subjects through conversation, photography, drawing, and painting the result has been a more profound insight into the complexity of gender presentation which in turn has supported the physical and psychological fabrication of a series of gender identity portraits. This collection is an analysis of gender appropriation, an investigation into identity presentation between and beyond the gender binary and a celebration of those who have the courage to be true to themselves and express who they are. Particular attention is paid to the evolution of modern masculinity and the increasingly widespread acceptance that what makes you male is not what makes you a man.